Inside a freezer in Columbia’s cell therapy lab, nearly a billion customized cells packed in a container no bigger than a yogurt cup may be the last chance to save the kidney of Dr. Pawel Muranski’s patient.

The kidney was only transplanted a few months prior. But because the patient’s immune system is suppressed to keep it from attacking the organ, a virus in the patient has reactivated and sparked a dangerous infection. No antiviral therapies exist to fight the virus causing the infection. And taking the patient off immunosuppressants will almost definitely lead to loss of the transplant.

The only option now is an experimental cell therapy—developed by Dr. Muranski and his colleagues at Columbia’s Cellular Immunotherapy Laboratory—that sets loose an army of T cells inside the patient to recognize and kill the virus.

Training Your Cells to Fight Cancer

Columbia’s Cell Therapy Lab is Customizing the Next Generation of Cell Therapies

Inside a freezer in Columbia’s cell therapy lab, nearly a billion customized cells packed in a container no bigger than a yogurt cup may be the last chance to save the kidney of Dr. Pawel Muranski’s patient.

The kidney was only transplanted a few months prior. But because the patient’s immune system is suppressed to keep it from attacking the organ, a virus in the patient has reactivated and sparked a dangerous infection. No antiviral therapies exist to fight the virus causing the infection. And taking the patient off immunosuppressants will almost definitely lead to loss of the transplant.

The only option now is an experimental cell therapy—developed by Dr. Muranski and his colleagues at Columbia’s Cellular Immunotherapy Laboratory—that sets loose an army of T cells inside the patient to recognize and kill the virus.

Pawel Muranski, MD

Assistant Professor of Medicine and of Pathology and Cell Biology, Vagelos College of Physicians and Surgeons

Director of Cellular Immunotherapy at NewYork-Presbyterian/Columbia University Irving Medical Center

Member, Tumor Biology and Microenvironment Program, Herbert Irving Comprehensive Cancer Center

Dr. Muranski, director of the Cellular Immunotherapy Laboratory at NewYork-Presbyterian/Columbia, saw the need for such cells when he worked at the National Institutes of Health, where some of the original immunotherapy strategies were developed, including cancer immunotherapy.

The experimental cell therapy is the first to be developed at Columbia, but Dr. Muranski hopes it’s just a start. His biggest goal is to develop new types of T-cell therapies to attack solid cancers, against which immunotherapies have generally failed.

“We’ve already seen success with cancer cell therapy, like CAR T cells which have cured some patients with B-cell malignancies. While other common cancers are still a challenge there is constant progress, and I think eventually we’ll be able to cure many more cancers with cell therapy.”

—Pawel Muranski, MD

T-cell Therapies to Kill Cancer

There are different types of cancer immunotherapy, but their approaches all follow or combine two important strategies: making it easier for the immune system to identify and target cancer cells or strengthening the immune system's response to help it attack cancer cells more effectively.

Compared to attacking cancer, using T cells to target viral infections is relatively straightforward, because our immune system is naturally poised to control viruses.

In recent years, CAR T therapies for blood cancers have been developed and approved by the FDA, but these T-cell therapies have not had much success with solid cancers.

CAR T-cell therapy works by re-engineering T cells to lock on to unique antigens on the surface of tumor cells. Solid cancers represent difficult targets for the immune system and CAR T cells are largely limited to recognizing only the surface molecules, while many cancer-associated antigens reside inside the tumor cells.

Dr. Muranski thinks that using naturally occurring T cells might be a better bet. His work focuses on a type of T cells called CD4+ T helper cells. These cells are the master orchestrators for the functionality of the entire immune system.

“T helper cells allow us to target cancer antigens that are not just on the surface of the cells, but also inside the cells,” he says. This is how normal T cells in the body typically recognize infected cells or cancer cells.

“Emerging data suggest that T helper cells can be really very powerful, and I think the majority of cancers can be targeted with T cells including T helper cells rather than with CAR T cells.”

Dr. Muranski arrived at Columbia in 2017 to set up Columbia’s first cell therapy facility where in-house therapies could be created for testing in patients. Few medical centers have such facilities, but that’s where new cell therapies are likely to be created.

“Many immunotherapies originated at academic institutions and then they are developed further by industry,” Dr. Muranski says. “We’re not trying to replicate what industry is doing. The idea is to innovate and produce the next generation of cell therapies.”

The virus-specific T-cell therapy for transplant patients is similar in concept to earlier experimental therapies, but is being produced much more rapidly. What previously took more than a month and huge vats of cell culture can now be accomplished in two weeks inside bioreactors smaller than a cup of coffee.

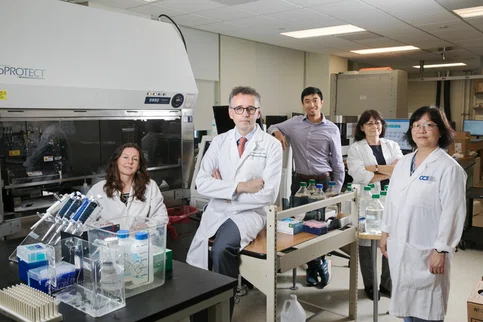

Dr. Pawel Muranski (center, foreground) with members of the Cellular Immunotherapy Laboratory, from left to right: Agata Jurewicz, Hei T. Chan, Rodica Ciubotariu, and Jian B. Pan.

The experience Dr. Muranski’s team has gained to create an experimental cell therapy for transplant patients has built the operational foundation for an experimental cancer immunotherapy program. Trials of new cell therapies that target cancer are now under preparation.

“We’ve already seen success with cancer cell therapy, like CAR T cells which have cured some patients with B-cell malignancies,” says Dr. Muranski. “While other common cancers are still a challenge there is constant progress, and I think eventually we’ll be able to cure many more cancers with cell therapy.”

Training Your Cells to Fight Cancer

Experimental Cell Therapy for Transplant Patients

Inside a freezer in Columbia’s cell therapy lab, nearly a billion customized cells packed in a container no bigger than a yogurt cup may be the last chance to save the kidney of Dr. Pawel Muranski’s patient.

The kidney was only transplanted a few months prior. But because the patient’s immune system is suppressed to keep it from attacking the organ, a virus in the patient has reactivated and sparked a dangerous infection. No antiviral therapies exist to fight the virus causing the infection. And taking the patient off immunosuppressants will almost definitely lead to loss of the transplant.

The only option now is an experimental cell therapy—developed by Dr. Muranski and his colleagues at Columbia’s Cellular Immunotherapy Laboratory—that sets loose an army of T cells inside the patient to recognize and kill the virus.

Pawel Muranski, MD

Dr. Muranski, director of the Cellular Immunotherapy Laboratory at NewYork-Presbyterian/Columbia, saw the need for such cells when he worked at the National Institutes of Health, where some of the original immunotherapy strategies were developed, including cancer immunotherapy.

The experimental cell therapy is the first to be developed at Columbia, but Dr. Muranski hopes it’s just a start. His biggest goal is to develop new types of T-cell therapies to attack solid cancers, against which immunotherapies have generally failed.

T-cell Therapies to Kill Cancer

“We’ve already seen success with cancer cell therapy, like CAR T cells which have cured some patients with B-cell malignancies. While other common cancers are still a challenge there is constant progress, and I think eventually we’ll be able to cure many more cancers with cell therapy.”

—Pawel Muranski, MD

Assistant Professor of Medicine and of Pathology and Cell Biology, Vagelos College of Physicians and Surgeons

Director of Cellular Immunotherapy at NewYork-Presbyterian/Columbia University Irving Medical Center

Member, Tumor Biology and Microenvironment Program, Herbert Irving Comprehensive Cancer Center

There are different types of cancer immunotherapy, but their approaches all follow or combine two important strategies: making it easier for the immune system to identify and target cancer cells or strengthening the immune system's response to help it attack cancer cells more effectively.

Compared to attacking cancer, using T cells to target viral infections is relatively straightforward, because our immune system is naturally poised to control viruses.

In recent years, CAR T therapies for blood cancers have been developed and approved by the FDA, but these T-cell therapies have not had much success with solid cancers. CAR T-cell therapy works by re-engineering T cells to lock on to unique antigens on the surface of tumor cells. Solid cancers represent difficult targets for the immune system and CAR T cells are largely limited to recognizing only the surface molecules, while many cancer-associated antigens reside inside the tumor cells.

Dr. Muranski thinks that using naturally occurring T cells might be a better bet. His work focuses on a type of T cells called CD4+ T helper cells. These cells are the master orchestrators for the functionality of the entire immune system.

“T helper cells allow us to target cancer antigens that are not just on the surface of the cells, but also inside the cells,” he says. This is how normal T cells in the body typically recognize infected cells or cancer cells.

“Emerging data suggest that T helper cells can be really very powerful, and I think the majority of cancers can be targeted with T cells including T helper cells rather than with CAR T cells.”

Dr. Muranski arrived at Columbia in 2017 to set up Columbia’s first cell therapy facility where in-house therapies could be created for testing in patients. Few medical centers have such facilities, but that’s where new cell therapies are likely to be created.

“Many immunotherapies originated at academic institutions and then they are developed further by industry,” Dr. Muranski says. “We’re not trying to replicate what industry is doing. The idea is to innovate and produce the next generation of cell therapies.”

The virus-specific T-cell therapy for transplant patients is similar in concept to earlier experimental therapies, but is being produced much more rapidly. What previously took more than a month and huge vats of cell culture can now be accomplished in two weeks inside bioreactors smaller than a cup of coffee.

The experience Dr. Muranski’s team has gained to create an experimental cell therapy for transplant patients has built the operational foundation for an experimental cancer immunotherapy program. Trials of new cell therapies that target cancer are now under preparation.

“We’ve already seen success with cancer cell therapy, like CAR T cells which have cured some patients with B-cell malignancies,” says Dr. Muranski. “While other common cancers are still a challenge there is constant progress, and I think eventually we’ll be able to cure many more cancers with cell therapy.”

Dr. Pawel Muranski (center, foreground) with members of the Cellular Immunotherapy Laboratory, from left to right:

Agata Jurewicz, Hei T. Chan, Rodica Ciubotariu, and Jian B. Pan.